Since 2012, I’ve reviewed over 1700 applications from startups hoping to join Startmate, the most successful startup accelerator in Australia. We’ve made 106 investments worth $600M+ as of March 2020 from these applications - a 6% acceptance rate for these budding tech companies.

Why Do Startups Fail?

The accelerator acceptance rate is so selective because we only choose the best of the best and invest in the businesses that we truly believe in. While it’s helpful to analyse the successful startups to understand why they’ve been chosen, I think it’s more interesting to look at the ones that DIDN’T get in. So what’s the difference between a successful startup and one that fails?

The problem is your idea. Why? Ideas solve problems. Insights build businesses.

There are too many people floating around with just ideas that have no insight around them.

After sitting through quite a few of the interviews I began to notice some common patterns amongst the founders who weren’t going to succeed in Startmate.

The overarching problem I found with founders or companies that didn’t have a good chance of success was that they didn’t have a unique insight about the problem they were working on.

Many were thinking in such simplistic ideas. Kinda like…

Problem: Too many people are obese

Solution: Build an app that helps them lose weight

So what is the problem with this?

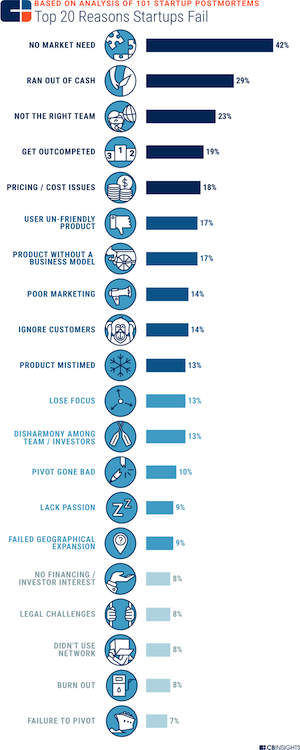

The problem is the problem! It is too general and the solution doesn’t actually solve anything in a meaningful way and when you don’t solve anything in a meaningful way it means there is no REAL need for your product and you will fail. But don’t just take my word for it….

The graphic above shows the top 20 reasons why startups fail. I would argue that you can tie every single one of them back to a vague problem and lack of insights and thats why they had no market need.

From Customer Development to Insight Development

The shortcut and simplest advice for launching a successful startup is building something you want that solves a real problem you understand a lot about.

If you have worked for 5+ years in procurement in the construction industry and now launch a startup that addresses a key pain point, chances are that you’ll already have a pretty good insight and intuition about what that problem is and how to solve it. It’s likely that you will get to product-market fit faster than somebody who doesn’t have that firsthand knowledge, giving you the advantage needed to raise your first round.

But that is not enough. It’s not just about solving a functional problem for people - it’s about connecting it to a core human need.

Customer Development and the Lean Startup

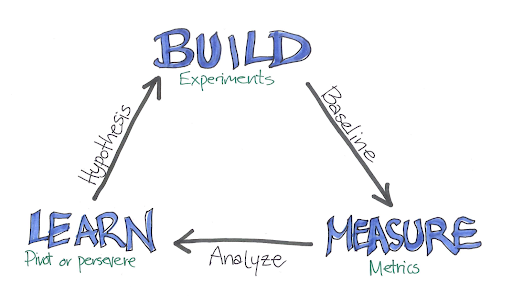

Most entrepreneurs have heard of the Lean Startup, a framework that prioritises customer development through hypothesis > build > test > measure > learn. While this is a valid method of building a business, it doesn’t dig deep enough to truly understand customer needs - the key differentiator between successful startups and failed ones.

The Lean Startup has bred a culture where all you have to do is come up with a hypothesis, build something to test that hypothesis and then it’s either validated and you keep it, or you take another guess at what to build / do next. Fail fast right? Well, partly.

Insight Development: What Makes Startups Successful

In order to launch a successful startup, you need to take it a step further. Build a better hypothesis and focus on insight development.

What is insight development? Insight development is the critical user research that comes before customer development that will get you to product-market fit significantly faster. It allows you to gain insights about the true outcomes and core human needs that drive your potential customers and where the next best alternatives fall short.

The lean startup tells us that the faster you can build and learn something, the faster you will get to product-market fit.

The one part that is missing from the lean startup is the unspoken fact that the better your hypothesis is, particularly your first one, the faster you will find product-market fit. People know how to do customer development and Eric Ries weaponised it in the Lean Startup, but Eric doesn’t really discuss the concept of insight development, which will help you make a better hypothesis and in turn, get to product-market fit faster.

This is what a journey to product-market fit looks like without insight development:

No doubt the speed at which you iterate or build stuff is important, but if your first guess of where to start is bad, it could take 10 or 20 product development cycles to get to the same place you would be if you had spent some time gaining insight about your customers at the beginning, allowing you to identify the true problem you’re trying to solve for your audience.

How To Use Insight Development To Launch A Tech Startup

The first step in insight development is understanding that people don't buy your product or service; they buy the desired outcome your product or service promises to deliver. The most compelling products are also the ones that link to one of the core human needs.

Made famous by Tony Robbins, the 6 core human needs are:

Certainty. The need for security, stability, and reliability.

Variety/Uncertainty. The need for change, stimulation, and challenge.

Significance. The need to feel acknowledged, recognised, and valued.

Love and Connection. The need to love and to feel loved, and to feel connection with others.

Growth. The need to grow, improve and develop, both in character and in spirit.

Contribution. The need to give, to help others, and to make a difference.

You need to develop insight around the problem. By connecting your idea to a core human need, you’ll be able to identify the true outcome your target audience hopes to gain from buying your product or service.

I normally define a particular outcome as a subset of a particular human need.

Let’s use the example of a gym membership. I only work with software and technology products but this concept works for developing all new products and everyone can relate to a real world example like a gym membership.

The first point is. You don’t really buy a gym membership to get access to a bunch of gym equipment or even a personal trainer. You buy the outcome that membership gives you. For example, two professional guys might be buying a gym membership for very different reasons.

Person 1: Is going to Burning Man and wants to look ripped on the Playa. That links Significance (#3) and maybe Love and Connection if he is trying to attract a partner (#4).

Person 2: Wants to be healthy and likes the way it sets him up for the day at work. This links to the core human need of Growth (#5).

So how can you take this desired outcome and apply it to a business idea?

Person 2: Desired outcome is general overall health and to set himself up for a productive day at work. To achieve this outcome, he joined a Crossfit gym that has multiple classes in the morning so it aligns with his professional schedule, and it’s full of a bunch of highly motivated people all interested in personal growth / improvement. However, there are only a few showers, which causes him to rush to work still a bit sweaty for his 9am meeting. This causes him to feel stressed and anxious - the antithesis of his desired outcome.

A great founder who has focused on insight development understands that this customer’s desired outcome is to set himself up for a great, high-performing day and realises the current alternatives fall short. The founder could solve the problem above by introducing a premium membership that would guarantee a shower straight after class and they would steal Person 2 as a customer. Throw in a 10-minute meditation after every class and you would seal the deal.

Building Better Hypotheses to Understand What People Truly Want

A hypothesis is really just a guess. So how do you make better guesses? The latest research in psychology and neuroscience by experts like Daniel Kahneman has uncovered that you learn through two modes of thinking.

We have System 1, which is fast, intuitive and emotional; let’s call it the ART.

And we have System 2, which is slower, more methodical and logical; THE SCIENCE.

The thing the Lean Startup missed is that its real purpose is to use a System 2-type process of hypothesis (test, build, learn) to actually improve your System 1 thinking (make better guesses).

The Lean Startup was built to overcome people just using gut instinct to build products. It injected some more methodical logic into the process, but I think it’s caused startups to not learn or care about the reason WHY each sprint / hypothesis succeeds or fails. Understanding the “why” is a crucial learning point for the collective intuition of the product, sales and marketing teams.

Instead of taking a step back to really think about why something succeeded or failed, people are just madly moving on to the next hypothesis in the backlog. Many startups have a backlog of experiments to run each month so when one fails, they just move on to the next and continually iterate at hyperspeed.

You need to blend the science of the latest A/B test with the intuition and observation of people using your product, and take that insight back into your team for collective learning. Watching the body language of people when they hear about your company or see the demo is a phenomenal type of early-stage feedback that you just don’t get from pushing out experiments.

I’ve had two tech startups in my life: one that failed called Booking Angel, and one that was wildly successful called Spreets. Both delivered new business to local companies, but my ability to understand and gain real insight into my customers’ problems and link it to a core human need is what caused Spreets to succeed.

Case Study #1: Booking Angel

2007 smartphone camera quality ;-)

My first tech startup, Booking Angel, was an online reservation system for restaurants. I started it in 2004 when I was actually running a restaurant in Sydney and noticed that it was a huge hassle to book reservations. People used to email me reservations and back then, we had to connect to the internet via dial-up, which disabled the phone line for credit card transactions. Sometimes I missed the emails and we even accidentally double booked tables because of this technology gap.

The solution I invented looked like this:

Diners booked online

It automatically phoned the restaurant during its opening hours

Delivered the reservation via voice and allowed the restaurant to say yes to accept or no to reject or an option to connect the customer on the phone to discuss alternate times

It automatically emailed the diners the confirmation

This addressed the functional problem of being able to accept online reservations without disrupting phone lines or double booking. At the time, I knew this was a huge pain point for every restaurant in Sydney, so surely this business idea would be a huge success, right?

As a matter of fact, Google recently built a much cooler version of the same thing and it seems to be a success. So the business idea was valid, but the reason why Booking Angel failed is because I pitched the idea to restaurants as a functional solution rather than focusing on the core human needs that it caters to.

One day, I got a call from one of our most popular restaurants saying they wanted to cancel. I had originally signed this restaurant up to Booking Angel under the premise that they would be able to accept online reservations without disrupting the phone lines - solving a functional problem. I asked why they wanted to cancel, and they said that Booking Angel was too expensive. I was charging them roughly $1 for each customer we brought them knowing that each individual diner would spend at least $40 there, so I was totally confused.

That same day I got a call from a new customer who had only been with us for a week. He wanted to refer me to a friend of his who owned a restaurant. He absolutely loved us. I couldn't work out why, so I asked him. He explained, “You promised that this would bring me new business. I didn’t believe you but we signed up anyway. As soon as it switched on, we had three new reservations straight away.”

The insight I was able to glean from this interaction was that restaurant owners didn’t want online reservations - they wanted more new business, feeding into the core human needs of growth and certainty.

Even though both restaurants were provided with the exact same product and service, the minor detail of stating that Booking Angel would enable them to take online reservations (functional problem solving) versus saying that it would bring them new business (reaching desired outcomes) set a completely different customer expectation. This slight difference in user experience highlights the key insight that the restaurant is happy to pay for an experience of getting new business as it links to the key human need of growth, and because you can switch it on and instantly generate more business, it also links to the core human need of certainty.

Unfortunately this insight didn’t come in time for me to pivot the business and Booking Angel failed, but I was able to take this experience and use it to inform my next venture: Spreets.

Case Study #2: Spreets

Now that I had caught onto the fact that understanding the customer’s desired outcome was the key to success, I was able to channel this insight into my next tech startup: Spreets. Spreets is a group buying site where users can find deals and discounts for local businesses in Australia. I launched Spreets in 2010 knowing that merchants on the B2B side wanted their outcomes to be tied to growth (new business) and certainty (that there will definitely be new business), but what about the consumer on the B2C side?

It seems obvious that consumers enjoy deal websites because they’re after the discount. But after investing time in user research, we learned that many customers were interested in the variety that Spreets had to offer. Trying new things, whether it’s skydiving or a painting class, was perceived as high risk for the average user. People had limited free time and were wary of wasting it on a new activity that had the potential to be disappointing or overpriced.

That’s why even though Spreets provided discounts to new activities, solving the functional problem of new activities being too expensive, the core human need that kept people coming back was the variety we provided. Our mission was to inspire people to try new and interesting things.

Understanding these core human needs on both sides of the marketplace allowed us to put together a winning sales and marketing strategy. It’s how we beat competitors who were spending $30M on advertising when we only raised $1.2M in total, as well as people that started with a database of 2M+ when we started with just a few. We understood the insights around our customers' problems which allowed us to convince better merchants to do deals with us, which allowed us to organically grow an audience with the better deals we had.

That’s why Yahoo!7 paid almost $40M dollars for us just 11 months after we launched.

Insight development is the key difference between startups that succeed and those that fail. Simply focusing on functional problems and iterating on quick hypotheses isn’t enough anymore. Being able to tie your company’s value prop to a core human need is what will allow you to develop solutions and product-market fit for an engaged community that will not only grow with you as you scale, but become repeat customers for life.

In my next post I will outline 5 actionable steps on how to do insight development and how you can use them to build a business.

Want to chat about insight development and core human needs? Disagree with everything I’ve written in this post? Either way, feel free to reach out at me@deanmcevoy.com.

Many thanks to Cameron Adams the co-founder and Chief Product Officer of Canva who gave me some great feedback on a draft of this article as well as David Kenney and Amy Yeh who provided input and made it much more readable.